Queer Activism in Public Space

“The truth is, I still cannot go outside without being afraid for my safety. There are few spaces where I do not experience harassment for the way I look.” - Alok Menon, Beyond the Gender Binary

Amsterdam Pride Celebration, 2018. Photo taken by Holly Hixson.

At their core, cities offer residents housing, amenities, access to a range of services, and opportunities for employment and recreation. At their best, they also act as a meeting place, facilitating social exchanges, providing critical spaces for democracy and representation, and supporting communities across ages, races, abilities, sexualities, and other identities. Policy, urban design, and planning have an important role to play in supporting inclusivity, social justice, and community empowerment for LGBTQ2S+ people. As recently introduced laws and policies across North America attempt to regulate queer people's access to healthcare, public space, and gender expression, the fight for representation and inclusion in cities continues. Cities as Sites of Queer Activism

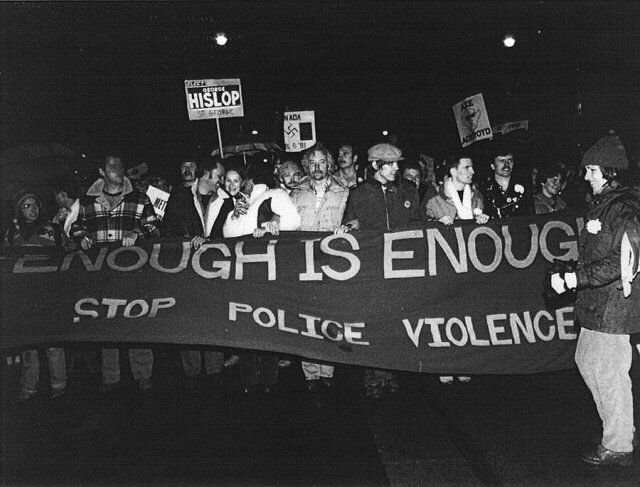

Cities have long been spaces of democracy and sites of struggle for LGBTQ2S+ activism. In 1969, the police raid of a New York City gay bar erupted into a series of protests known as the Stonewall Uprisings. Stonewall was the culmination of many years of (less popularized) LGBTQ+ activism and it fundamentally altered the discourse around queer activism in the United States. In Canada in 1981, 200 police raided several gay bathhouses in Toronto resulting in the arrest and humiliation of 300 men. Despite the Canadian government “decriminalizing” homosexuality in 1969, queer folks could still be charged with a number of offenses that related directly to their sexuality, and bathhouses at the time represented a place where many LGBTQ+ individuals could exist without being outed or reprimanded. Now known as the Toronto Raids, the raids led to widespread protests in public space against the discrimination and persecution faced by queer people and represented a turning point in LGBTQ+ activism in the country. To this day, Pride parades envelop streets around the world to foster community and honour the legacy of queer people (particularly Black and brown trans folks) who paved the way with their activism. It’s also a time for queer people to take up public space and express their identity however they see fit. Given that LGBTQ2S+ people still struggle against police brutality, harassment, discrimination, and criminalization based on their identity in public, pride is an exercise in visibility, and a celebration of queer existence. Image of Protesters responding to the Toronto Raids in 1981, Photo Credit: Pink Triangle Press

Recent Attacks on LGBTQ2S+ Rights

With laws and regulations being introduced across North America aimed at limiting the rights of queer people, the fight for acceptance and legitimacy continues for queer communities. In March 2023, Tennessee became the first state to explicitly ban drag shows in public spaces, with at least fourteen other states following suit and introducing anti-drag bills. More than two dozen bills have been filed in the US to ban transgender people from using bathrooms that match their gender identity. Recent changes to New Brunswick’s Policy 713, mean teachers are no longer required to use the preferred pronouns or names of transgender or non-binary students under the age of 16 in schools. These proposals are among a record number of bills filed to limit or ban gender-affirming healthcare for minors, ban transgender girls from participating in school sports, and banning teachers from creating a supportive and inclusive environment within schools (See: Florida’s Don’t Say Gay bill). An All Persons Restroom in Toronto, ON. Photo taken by Doolin O’Reilly.

Safety in Public Space

Alongside an increasingly hostile political environment, city spaces have a critical role to play as places to exercise democracy and public participation in service of queer liberation. We know that women have dramatically different experiences in public space and on public transport than men. Queer folks, particularly individuals with multiple marginalized identities, also have unique experiences in cities. Yet, urban planning doesn’t often view space from the lens of sexual identity or gender beyond the binary. A study on Gender-Based Violence in Youth which included over 500 LGBTQ2+ Youth in Canada found that participants consistently highlighted experiencing fear in public and expressed how the threat of violence impacted their safety and sense of safety in public. This was particularly pronounced for gender non-conforming youth and LGBTQ2+ youth who also identified as racialized. Finally, they found that many youth expressed a hesitation to go out in public and increased isolation as a result. In 2020, Statistics Canada found that transgender individuals were more likely to have experienced violence since age 15, and also more likely to experience inappropriate behaviours in public, online and at work than cisgender Canadians.As Alok Menon, acclaimed author and queer activist said in their poem, The Camera Cannot Walk Us Home, “Gender non-conformity is never allowed to be, it must always be doing. I was not allowed to be just another human walking down the street. My appearance becomes an agenda becomes an attack. (This is how they justify their aggression to us as self-defense.)” Pride flag and roses in Amsterdam, NL. Photo taken by Holly Hixson.

Inclusion Doesn’t End with Pride

The list of actions cities can take to improve the lives of LGBTQ2S+ people is extensive. To start, cities must work to create and protect quality affordable housing, and invest in communities by defunding the police. Next, cities must work to allow LGBTQ2S+ people to exist in public safely by “queering” public space, supporting design principles that are based on the experiences of non-binary and trans folks, and actively engaging the LGBTQ2S+ community in planning and development. Finally, cities should work to celebrate and honour queer identity throughout the year through heritage projects and public art to signal inclusion, acceptance and representation of LGBTQ+ activism that was hard earned on these streets. The fight for queer liberation is nowhere near over, and cities have an important role to play in uplifting people of all gender identities and sexualities all year round. Iconic multi-year art installation in Montreal’s Gay Village. Photo taken by Holly Hixson.

Resources

https://culturehouse.medium.com/we-need-queer-urbanism-aee5d5934d40

https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2019/06/us/stonewall-pride-fred-mcdarrah-cnnphotos/

https://xtramagazine.com/power/toronto-bathhouse-raids-40-years-194590

https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/queering-public-space

https://theconversation.com/the-queer-city-how-to-design-more-inclusive-public-space-161088

https://theconversation.com/the-queer-city-how-to-design-more-inclusive-public-space-161088

https://www.alokvmenon.com/blog/2021/5/2/the-camera-cannot-walk-us-home

https://vancouver.ca/parks-recreation-culture/park-board-pride.aspx